Zen garden

枯山水

Motif

Why are Zen gardens made of rocks?

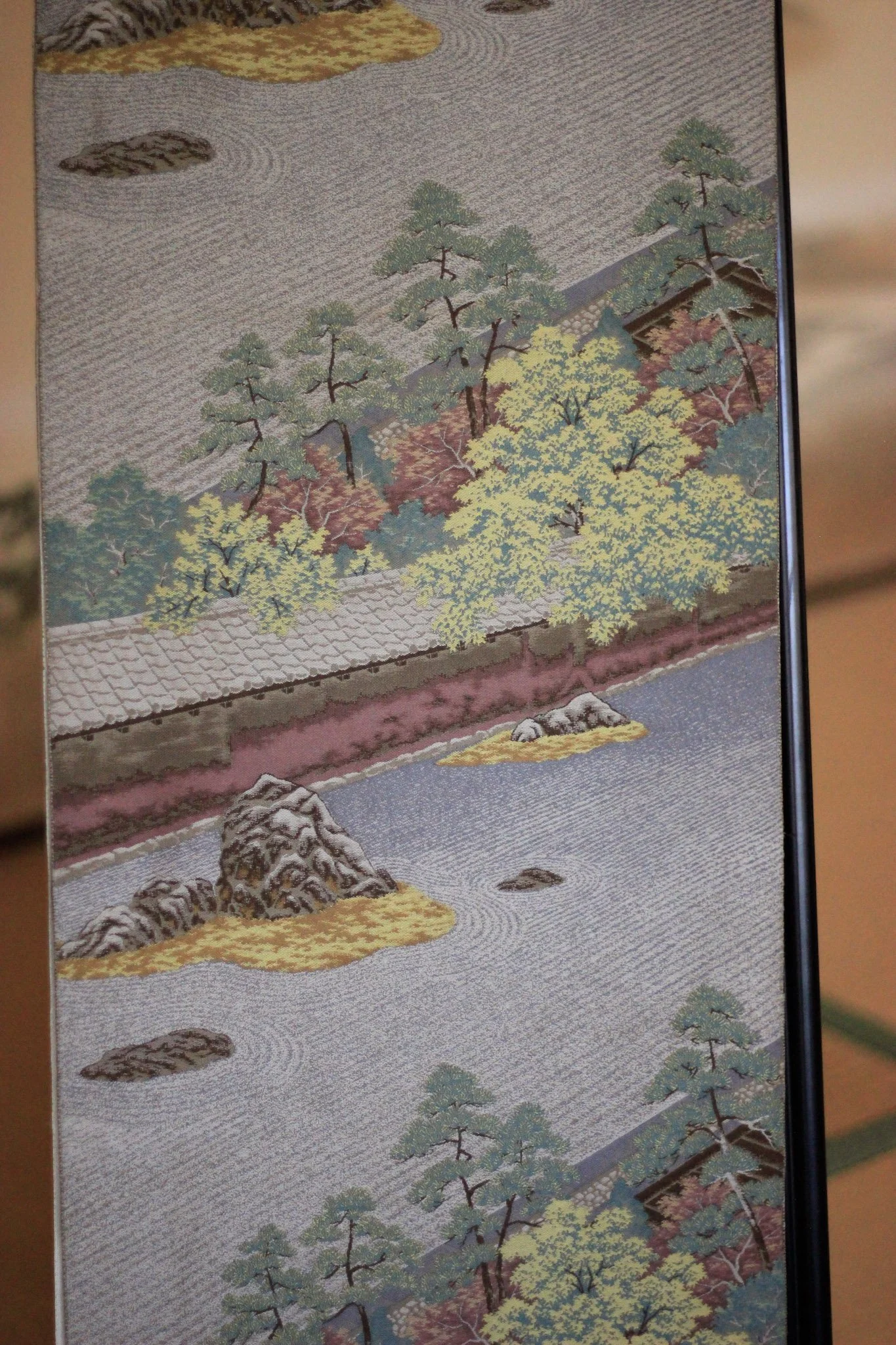

Have you ever wondered? One of the most iconic examples of this unique landscape style can be found at Daisen-in, a sub-temple of Kyoto’s Daitoku-ji complex. Its carefully placed rocks and meticulously raked gravel have inspired artists, monks, and textile designers for centuries, including the motif featured on this obi I believe.

Zen gardens, or karesansui (枯山水), are built using rocks and gravel to represent nature in its most abstract form. Rocks symbolize mountains or islands, while raked gravel evokes flowing water, rivers, waves, or seas. But, beyond symbolism, these gardens are deeply rooted in Zen Buddhist philosophy.

Unlike traditional gardens, Zen gardens aren’t meant for strolling but for quiet contemplation. Their minimalist landscapes encourages introspection and meditation, inviting the viewer to pause, reflect, and reconnect with the present moment. The repetitive act of raking the gravel is itself a meditative practice.

Rather than replicating nature literally, Zen gardens suggest it. Rocks become metaphors, and negative space becomes meaningful. To me, this approach also aligns with wabi-sabi, the Japanese aesthetic that finds beauty in simplicity, imperfection, and transience.

Twins obi

To my surprise, I didn’t find just one but two obi featuring this exact same Zen garden motif. Each is rendered in a different color palette: one evokes the deep red and earthy tones of autumn; the other captures the soft, muted hues of late winter giving way to early spring. Both are woven in retro-inspired colors, lending them a gentle, nostalgic atmosphere, as if they’re quietly remembering a landscape seen long ago.

Zen garden obi - Autumn

Zen garden obi - Winter

Textile

Like many traditional Japanese crafts, Shōha-ori has its origins in China and was later reimagined through a uniquely Japanese lens. This refined textile traces its roots to the Ming Dynasty and was introduced to Japan during the late 16th century. It gained popularity thanks to the poet and tea master Jōha Satomura (里村紹巴, 1552–1604, Nara), whose name inspired the term Shōha-ori (Jōha → Shōha).

Woven with tightly twisted warp and weft threads, Shōha-ori is prized for its smooth, lightweight, and flexible texture. Originally used to wrap tea utensils in the tea ceremony, it eventually became a favorite among kimono wearers for its ease of tying and subtle, intricate patterns. Even today, Shōha-ori obi are highly valued, some pieces can sell for thousands of dollars.

Composition: 100% silk

Framing

When ordering, make sure to indicate whether you prefer Autumn or Winter colours. When ordering a Phone bag or a Bumbag, you can choose the details and colours of the motif you would like to feature on your bag. A bigger design like the Computer bag or the Weekender will allow the entire motif to show.

Previously made in this fabric

Travel pouch (large)

Weekender

Be the next to order a bag in this fabric!

Choose your bag design from the original collection.